When most people think of ancient Egypt, images of pyramids, pharaohs, and elaborate tombs come to mind. Rarely do we consider the everyday lives of the people who lived along the Nile—what they wore, how they cared for their clothing, or the art of laundry that kept them looking presentable in a harsh desert environment. Yet, the history of laundry in ancient Egypt is a fascinating window into both their ingenuity and their cultural values. The Egyptians’ approach to cleanliness was not merely practical; it was intertwined with religion, social status, and personal dignity, making laundry a task that was both functional and symbolic.

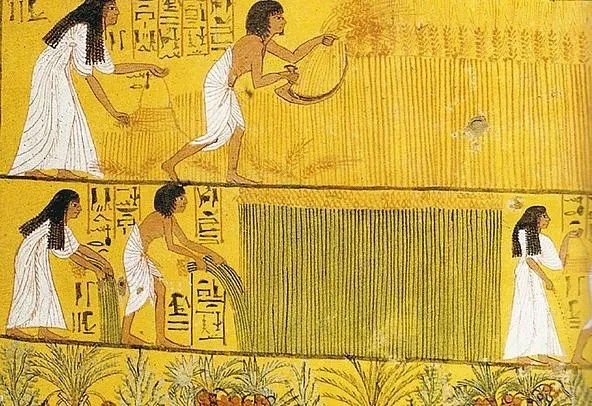

Linen was the textile of choice in ancient Egypt, prized for its light, breathable qualities that suited the hot climate. Linen was made from flax, a plant that thrived along the fertile banks of the Nile. The process of turning flax into wearable cloth was labor-intensive and highly skilled. After harvesting, flax stalks were soaked in water—a process known as retting—to loosen the fibers. Once the fibers were separated, they were dried, combed, and spun into thread. Finally, the threads were woven into sheets of linen, ranging from coarse weaves used for everyday garments to fine, delicate cloths worn by the elite.

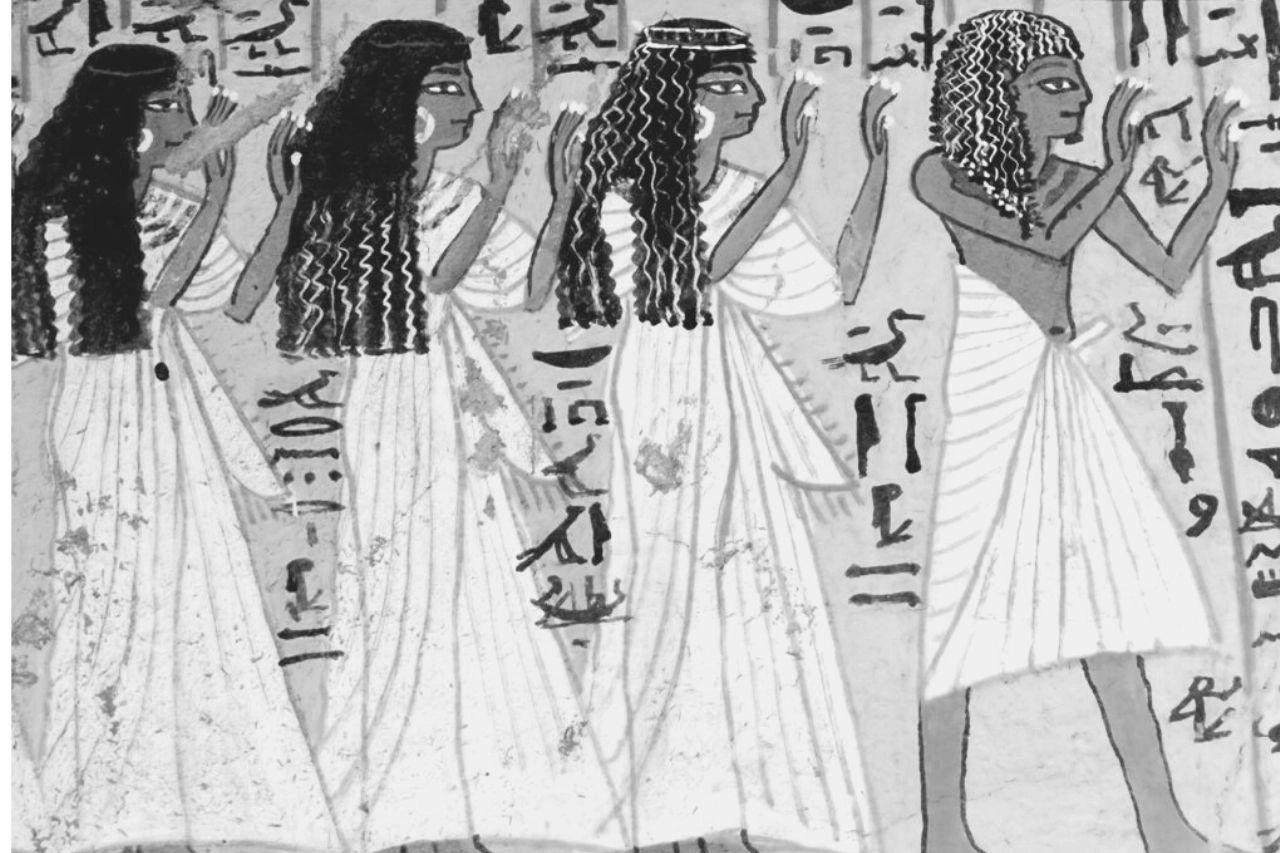

The Egyptians held cleanliness in high regard, linking it to health, beauty, and even spiritual purity. Cleanliness was so significant that bathing and laundering were not only daily routines but also integrated into religious rituals. Priests, for example, were required to wear spotless linen robes when performing sacred ceremonies. Thus, laundering was a culturally vital practice, extending beyond mere hygiene to encompass spiritual and social identity.

So how did the Egyptians actually wash their clothes? The methods were ingenious given the lack of modern technology. One of the most common techniques involved soaking garments in water combined with naturally occurring minerals. Natron, a naturally occurring compound consisting primarily of sodium carbonate, sodium bicarbonate, and sodium chloride, played a central role. Natron was known for its cleansing and bleaching properties. Garments would be immersed in a solution of water and powdered natron, allowing the mineral to help remove oils, dirt, and organic matter. After soaking, the fabric was thoroughly rinsed to remove residues, leaving it bright and clean.

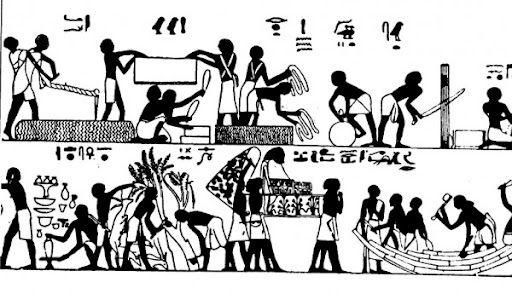

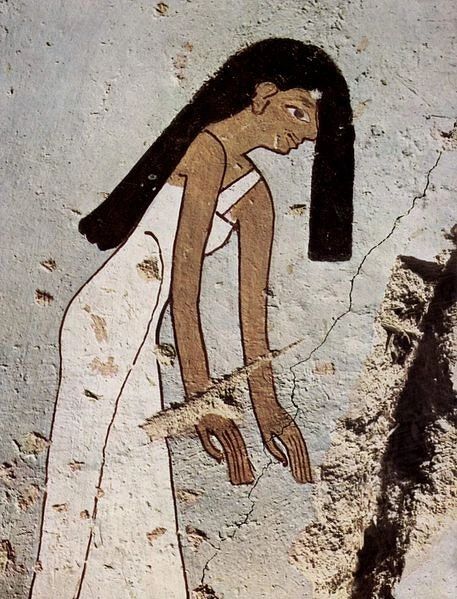

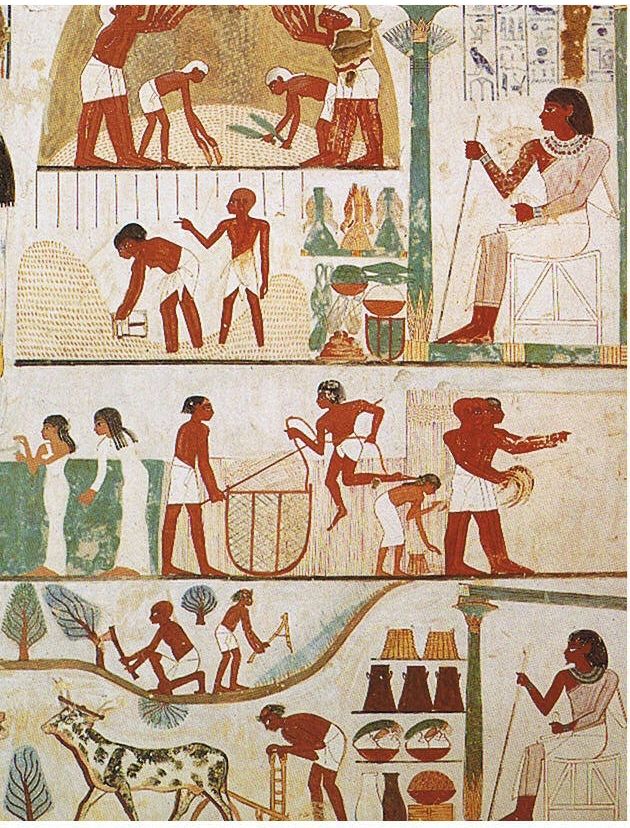

For more delicate or heavily soiled linens, the Egyptians employed a technique called “fulling.” This process involved beating or trampling the fabric in water, sometimes using wooden mallets or even the feet of the washer. Fulling served two purposes: it cleansed the fabric and also compacted the fibers, making the linen denser, more durable, and easier to wear. Archaeological evidence suggests that communal washing areas were common, where multiple women might work together to launder clothing, making it a social activity as well as a necessary chore.

Sunlight played an important role in the bleaching process. After washing, garments were often spread out in the sun to dry. The intense Egyptian sunlight not only dried the linen but also further whitened the fibers. The Egyptians understood the natural power of ultraviolet rays in breaking down stains and brightening cloth, long before the chemical bleach became widely known. This combination of mineral solutions, mechanical agitation, and solar exposure produced garments that were both hygienic and visually striking.

Interestingly, laundry practices were closely linked to social hierarchy. Fine, white linen was a symbol of wealth and status, while coarser fabrics were worn by laborers and lower-class citizens. The elite could afford to have their garments washed more frequently and by skilled workers, ensuring the finest appearance. Tomb paintings and reliefs depict servants attending to the clothes of pharaohs and nobles, illustrating the labor-intensive nature of maintaining a pristine wardrobe in a society that prized personal presentation.

Perfumes and oils were often applied to laundered fabrics as well. These were derived from local plants and flowers and served multiple purposes: masking odors, softening stiff linen, and adding a touch of luxury to everyday attire. In many ways, laundry was as much about enhancing sensory appeal as it was about cleanliness. Even the act of folding and storing garments was performed with care, with garments often kept in linen sacks or wooden chests to protect them from dust, moisture, and insects.

The religious dimension of laundry cannot be overstated. Cleanliness was associated with Ma’at, the concept of truth, balance, and cosmic order. Maintaining clean clothing was therefore an extension of maintaining moral and spiritual order. Priests washed not only their own garments but also ceremonial cloths used in temples, connecting the act of laundering directly to the sacred life of the community. Funerary rituals also incorporated linen. The careful wrapping of mummies in meticulously laundered linen, sometimes bleached and perfumed, demonstrates the Egyptians’ belief in the transformative and protective power of clean fabric.

Linen’s durability also meant that laundering was sometimes surprisingly sustainable. Fabrics could be washed repeatedly, using the natural properties of natron and sunlight, without the fibers quickly breaking down. This longevity allowed families to preserve garments over many years, and garments often passed from one generation to the next. The combination of careful cleaning, bleaching, and perfuming ensured that clothing could maintain both its function and its aesthetic appeal over time.

Beyond domestic and ceremonial contexts, laundry also reflected broader environmental adaptation. The Egyptians made use of the Nile not only for irrigation and transportation but also as a resource for washing. The river’s waters provided the perfect medium for soaking and rinsing garments, while its alkaline sediment likely contributed to softening fabrics and enhancing the cleaning process. Evidence from tomb murals and papyri indicates that water management and laundry were intertwined, with washing tasks sometimes scheduled according to seasonal variations in the Nile’s flow.

Interestingly, the labor of laundering was primarily undertaken by women, a fact that underscores the gendered division of labor in ancient Egyptian society. Women, especially those in households of means, were responsible for managing the cleanliness of the family’s clothing, linens, and textiles. In elite households, this work could be delegated to servants, while in more modest homes, family members themselves performed the washing, fulling, and drying. This responsibility extended beyond mere practicality; it was a key part of maintaining household honor, demonstrating diligence, and ensuring social respectability.

The tools of ancient Egyptian laundry were minimal yet effective. Wooden beaters, large basins, and drying racks constructed from reeds or timber provided the infrastructure for daily laundering. The Egyptians also understood the importance of fabric care: avoiding excessive friction, protecting delicate embroidery, and preserving the structural integrity of linen fibers. Their methods combined tactile skill, chemical knowledge (in the form of mineral cleaning agents), and environmental awareness (sunlight and water management), creating a sophisticated system that meets modern standards of efficiency and sustainability in principle if not in convenience.

As remarkable as these techniques were, the cultural significance of laundry in ancient Egypt went far beyond mere utility. Clean, white linen was a visual representation of civility, spiritual alignment, and societal hierarchy. The meticulous care invested in laundering garments was a reflection of the broader Egyptian worldview, where order, harmony, and cleanliness were deeply intertwined with moral and spiritual order. In many ways, the simple act of washing clothes became a ritualized practice that connected everyday life to cosmic principles.

The laundry practices of ancient Egypt reveal a society deeply invested in cleanliness, aesthetics, and symbolic meaning. From the cultivation of flax along the Nile to the fulling and bleaching of linen in communal washing areas, every step of the process reflected both practicality and cultural values. The Egyptians’ ingenious use of natural cleaning agents, sunlight, and mechanical action illustrates their understanding of chemistry and physics, long before these sciences were formally recognized. Moreover, laundry was a social, spiritual, and gendered activity that reinforced household management, religious observance, and social hierarchy.

Final Spin

Ancient Egyptian laundry was more than just washing clothes—it was an art form, a ritual, and a statement of identity. So the next time you load a washing machine, remember: you’re participating in a practice that’s thousands of years old, connecting your clean shirts and sheets to a civilization that made order, beauty, and purity a daily affair. Who knew doing laundry could be so historically glamorous?

Support The Laundry Club Blog – I can’t mummify your laundry in sacred linen or summon natron from the Nile—but I can unearth the secrets of ancient Egyptian spin cycles. If you learned something new (or at least smiled picturing a pharaoh folding towels), consider tossing a coin into my modern-day offering basket.

Leave a comment