There’s something deeply symbolic about laundry. It’s one of the most universal human chores, yet often overlooked for its spiritual, cultural, and emotional significance. We wash to prepare, to purify, to preserve. We wash to transition—from work to rest, from life to death. And when it comes to death, many cultures around the world have fascinating laundry-related traditions tied to the afterlife. These rituals offer glimpses into how the living maintain connections to the dead—by folding, scrubbing, and spinning memory into motion.

So, let’s pour a little lavender rinse in the cosmic wash basin and spin through some traditions where laundry meets the dead.

Japan: The White Kimono and Death Laundry

In Japan, death is handled with meticulous care, and laundry plays a quiet yet powerful role in the funeral process. The deceased is often dressed in a white kimono called a kyōkatabira—a symbolic death robe traditionally worn by pilgrims and the dead alike. Before being dressed, the body is cleaned, sometimes by close family members, in a ritualistic bath called yukan. Towels and cloths used in this process are either cleansed thoroughly or burned. Cleanliness in death is a final gesture of love, honor, and spiritual release.

This is a laundry ritual of transition—washing away the earthly residue so the soul may journey unburdened.

Mexico: Día de los Muertos and the Scent of Soap

In Mexico, Día de los Muertos (Day of the Dead) celebrations overflow with color, marigolds, and incense—but also with clean linens. Homes are cleaned, and fresh sheets and towels are set out in preparation for the spirits’ return. Some families even wash and iron clothes once belonging to the deceased, displaying them on ofrendas (altars), alongside sugar skulls and candles.

Clean laundry becomes a symbol of welcome—a way to say, “We remember you, and we’ve made everything fresh for your visit.” It’s the unspoken hospitality of the afterlife.

Madagascar: Famadihana and the Wrapping of Ancestors

In Madagascar, the Merina people perform famadihana, or the “Turning of the Bones,” where they exhume the remains of loved ones, rewrap them in fresh cloth, and dance with the bodies in joyful remembrance. These cloths, called lamba mena, are often washed, blessed, or newly woven. The act of rewrapping isn’t just practical—it’s profoundly spiritual. Clean cloth honors the dead and refreshes the bond between generations.

Imagine the weight of that laundry: the sacred responsibility of caring for the fabric that once held the dead.

Jewish Tahara: Purification Before Burial

In Jewish tradition, tahara is the ritual purification of a deceased body, carried out by a group known as the chevra kadisha (holy society). The body is washed with warm water and carefully dried with linen or cotton cloths. It’s then dressed in simple white shrouds called tachrichim.

Everything used in the process is either washed and reused for others or buried along with the body. Laundry here is an act of quiet devotion—returning the person to the earth in dignity and ritual cleanliness.

Ghana: Funeral Fashion and Fabric Tributes

In parts of Ghana, funerals are vibrant celebrations of life. Attendees wear coordinated outfits made from patterned fabrics that commemorate the dead—sometimes even with the name or face of the deceased printed on the cloth. These garments are pressed, starched, and immaculately laundered for the event. Afterward, they may be washed and repurposed, or kept in special trunks as family heirlooms.

Here, laundry is a performance—bold, proud, and alive with memory.

The Philippines: Laundry as a Mourning Clock

In Filipino households, especially in rural provinces, there are beliefs tied to laundry during mourning. It’s often taboo to wash clothes during a wake or within a set mourning period—sometimes for as long as nine days. Washing too soon is thought to “wash away the soul” or disturb the spirit’s peaceful passage.

Laundry becomes more than a chore—it’s a clock, measuring grief in days and decisions.

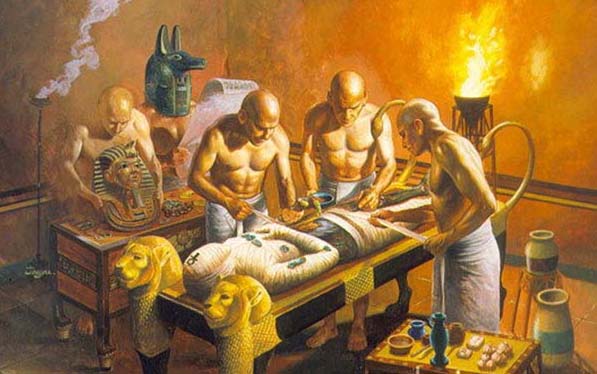

Ancient Egypt: Mummification and the Ultimate Wrapping

While not laundry in the modern sense, the wrapping of mummies in ancient Egypt was a profoundly sacred act. Linen—washed, blessed, and sometimes perfumed—was used to encase the dead, layer by layer. Each piece could be inscribed with spells or prayers. The cloth wasn’t just burial gear; it was spiritual armor.

Imagine folding sheet after sheet, not for bedtime, but for eternity.

Slavic Traditions: Rusalki and the Wet Clothes of Spirits

In Slavic folklore, rusalki are water spirits believed to be the souls of young women who died tragically. They’re often seen washing clothes by rivers or hanging dripping laundry on willow trees. To come upon a rusalka doing laundry was ominous—these spirits might lure the living into the water.

Here, laundry is haunted—wringing sorrow into wet cloth and binding spirit to shore.

Haiti: Vodou, Veves, and Sacred Linens

In Haitian Vodou funerary rites, white linens are draped on altars, laid under caskets, and waved during rituals. The dead are honored with washed and consecrated cloth, sometimes embroidered or knotted with symbols. Veves, ritual symbols drawn with cornmeal or chalk, may be outlined on white sheets during spiritual ceremonies.

The laundry is imbued with power. It carries the scent of spirit, salt, and soap.

Appalachia and Southern Lore: Signs in the Sheets

In the American South, particularly in Appalachia, folklore around death often involves laundry. One superstition warns not to hang sheets or white clothing on the line if someone is dying in the home—it could invite death in. Others believe you must wash and change the bed linens immediately after someone passes, to keep the spirit from lingering.

Here, laundry is ghost protocol—folded with caution and whispered beliefs.

Final Spin Cycle: Washing Grief, Folding Memory

What unites all these customs is the humble yet powerful presence of cloth. Washed, folded, wrapped, or hung, it serves as a bridge between the realms of the living and the dead. It cradles our bodies in life and accompanies us in death. Laundry, in these moments, becomes more than a routine—it becomes ritual.

Maybe the next time you hang a shirt to dry or fold a clean sheet, you’ll pause and think about the millions of hands before you who did the same—for love, for honor, for grief.

Cleanliness might be next to godliness, but in these stories, it’s next to memory.

Leave a comment