Once upon a time, before spin cycles and scented pods, the sound of laundry was the steady rhythm of fabric striking water — the echo of women’s voices along a riverbank, the slap of linen against stone, and the creak of a wooden bat as it beat out the week’s dirt.

The metal washboard and hard bar soap — now symbols of “old-fashioned laundry” — were once the shiny new innovations of the 1800s. But long before those ridged boards made their debut, laundry was a task of endurance, ritual, and community.

This is a look back — at how people washed and dried their clothing from the medieval period through the 19th century — an era when laundry was done by hand, by heart, and by sheer will.

Rivers, Rocks, and the Rhythm of Washing

For centuries, rivers were the original laundromats. Even today, in many parts of the world, washing clothes in a flowing river remains the norm — a tradition that echoes back through generations.

In Europe and North America, riverside washing continued well into the 19th century, even when the river was crusted over with ice. Stains were often treated at home first, and then women would carry the heavy baskets to the water’s edge.

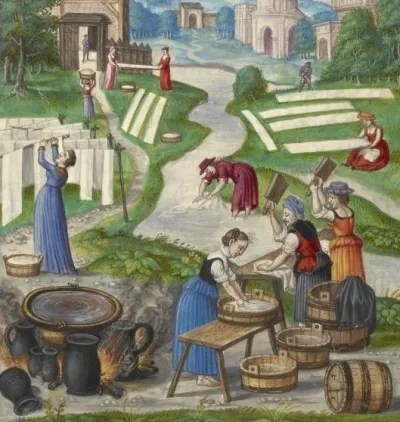

They brought tools of the trade: washing bats, beetles, and boards. These weren’t fancy contraptions — just pieces of wood used to pound, stir, and scrub. Beating the dirt out of fabric was called possing, and over time, sticks evolved into “possing sticks” or washing dollies — the ancestors of our modern agitators.

If no board was handy, a flat river rock would do. Clothes were slapped, trampled, and twisted clean. It was hard work, rhythmic work — part labor, part meditation.

Laundry in those days wasn’t so different from textile finishing. Freshly woven fabrics were treated much the same way — soaked, scrubbed, pounded, and stretched. It was all about strength, both in the cloth and in the hands that washed it.

Lye, Bucking, and the Long Soak

Before detergent, there was lye — a potent mix made from ashes and water. Sometimes, yes, urine too. (And yes, that’s true — ammonia-rich urine was once a prized laundry aid.)

Laundry wasn’t a weekly affair. The “big wash” happened every few weeks, sometimes even months apart. The process was called bucking — soaking white or off-white fabrics in lye to whiten and cleanse.

Colored fabrics were rare, and whites were prized — though “white” was a loose term back then. Ashes and urine helped strip away grease and stains, leaving cloth brighter and fresher.

Soap, when used, was often homemade — a soft soap from animal fat and lye. The poorest families rarely used it, while wealthier households used soap sparingly, saving it for finer garments and collars. By the 18th century, soap became more common, though still considered a luxury item.

One traveler to England in 1698 noted his surprise:

“All their linen, coarse and fine, is wash’d with soap… When you are in a place where the linen can be rins’d in any large water, the stink of the black soap is almost all clear’d away.”

— M. Misson’s Memoirs and Observations in his Travels over England

The scent of soap was a small price to pay for cleanliness — though, for many, it still smelled like work.

Drying, Bleaching, and the Great Wash

After all that scrubbing came the Grand Wash — a kind of spring cleaning for linens and clothing. Soaked, bucked, and rinsed, fabrics were carried outside to dry and bleach under the open sky.

Sunshine was nature’s bleach. Laundry was spread out across grass or bushes, sprinkled occasionally with water or a dash of lye to encourage the whitening process.

Towns and manors often had a bleaching green — an expanse of trimmed grass reserved for drying linens. In early America, settlers created communal greens for this same purpose. Laundry wasn’t just a chore — it was social, public, and sometimes even celebratory.

Clotheslines as we know them didn’t become common until later. Paintings from the 16th century show sheets draped over hedges or frames, not clipped with pegs (which didn’t appear until the 18th century).

Indoors, ropes or wooden frames held linens on rainy days. But the smell of sun-dried fabric — that clean, grassy scent — was the real prize.

Final Spin

The history of laundry isn’t just about soap and water — it’s a story of survival, invention, and rhythm. From river rocks to ridged boards, every generation found a way to make the load a little lighter.

When we pour detergent into a high-efficiency machine today, we’re still part of that lineage — the long tradition of people who refused to live with dirty laundry.

Here’s to those who soaked, scrubbed, and beat the world clean — one shirt, one sheet, one stubborn stain at a time.

Support The Laundry Club: Dirty Laundry and help keep these stories of soap, sweat, and survival alive: paypal.me/TheLaundryClub

Leave a comment